This article is going to serve as my personal reference on this topic. Since I’ve always wanted to write about it and just finished Yuma Kurogome’s course on Advance Binary Deobfuscation, I thought it would be a good time to write notes regarding what I learned in this course with a fresh state of mind on the subject matter for future reference.

Introduction #

There are close to 31 known code transformations. However, In this article we will focus on grouping these transformation in categories based on their behavior, and we will cover some of the most relevant techniques today on a conceptual point of view. We will be also covering practical approaches to the aforementioned techniques using the reverse engineering framework MIASM (0.1.3.dev39).

Despite the large number of transformations, obfuscation techniques can be group up into 3 different categories:

- Confusion oriented:

- Unreachable Code Insertion

- Dead Code Insertion

- Syntax Modification

- Instruction Substitution

- Constant Folding/Unfolding

- Semantic Modification

- Opaque Predicates

- Range Dividers

- Virtualization

- Control Flow Flattening

We will be discussing each of these techniques on a conceptual level, although we will be also covering practical examples. The purpose of this article is to crystallize concepts instead of being a strict technical reference, although further technical reading will be linked all throughout the article along with practical implementations on how to remediate some of these techniques.

## Unreachable/Dead Code, Constant Unfolding and Instruction Substitution

In this section we will be covering 3 different transformations which have a close correlation between one another, and consequently a similar approach for circumvention.

-

Unreachable Code: is defined as inserted code into a target application which is never going to be executed, serving the purpose of an unexpensive way of distracting the analyst for a few minutes. an example of Junk code is the following:

jz loc_key1 ; lets imagine this conditional branch is not really conditional xor eax, eax ; * this will never execute pushf ; * pop ebx ; * and ebx, 0x100 ; * cmp ebx, 0x100 ; * je loc_key2 ; * loc_key1:

-

Dead Code: is defined as inserted code into a target application which, although it may be executed, it does not change the original control flow of the program. Again this technique’s pupose is to just confuse the analyst to make him/her spend a bit more time understanding the purpose of the aforementioned instructions. The following is an example:

mov edx, 0xdeadc00d ; * this specific instruction is deadcode mov eax, [ebp+arg_4] mov ecx, [ebp+arg_0] mov edx, 5 ; * edx gets overriden here, also deadcode mov [ebp+var_4], ecx mov [ebp+var_8], eax

-

Instruction Substitution: defined as to replace a given set of instructions with another more complex set of instructions with identical semantic meaning. This kind of techniques have been heavely employed by metamorphic code engines in the past and may highly affect the legibility of the affected code. Lets imagine that originally we have the following set of instructions:

This set of instruction can be transform to the following one, being much harder to interpret and understand having the same semantic meaning:mov eax, [ebp+var_8] add eax, [ebp+var_C] add eax, [ebp+var_10] add eax, [ebp+var_4]mov eax, [ebp+var_C] mov edx, [ebp+var_10] sub eax, 2598A32Bh add eax, edx add eax, 2598A32Bh mov edx, [ebp+var_4] mov esi, ecx sub esi, eax mov eax, ecx sub eax, edx add esi, eax mov eax, ecx sub eax, esi mov edx,[ebp+var_8] sub ecx, edx sub eax, ecx

Circumvention #

In order to mitigate these transformations we can do a variety of techniques based on Data Flow Analysis. Before we introduce these techniques, is important to understand that in order to succesfully implement Data Flow Analysis strategies we have to rely on a Intermediate Representation of the subject code. Compilers also rely on IRs to apply their program synthesis and code optimitations capabilities. In other words, We can deobfuscate these transformations by using the same techniques used by compilers for their own optimization purposes.

These techniques are the following:

Reachable Definition Analysis #

- Forward dataflow analysis

- Analyze where the value of each variable was defined when a certain point in the program was reached

- Application:

- Constant propagation/folding

- Transform expressions

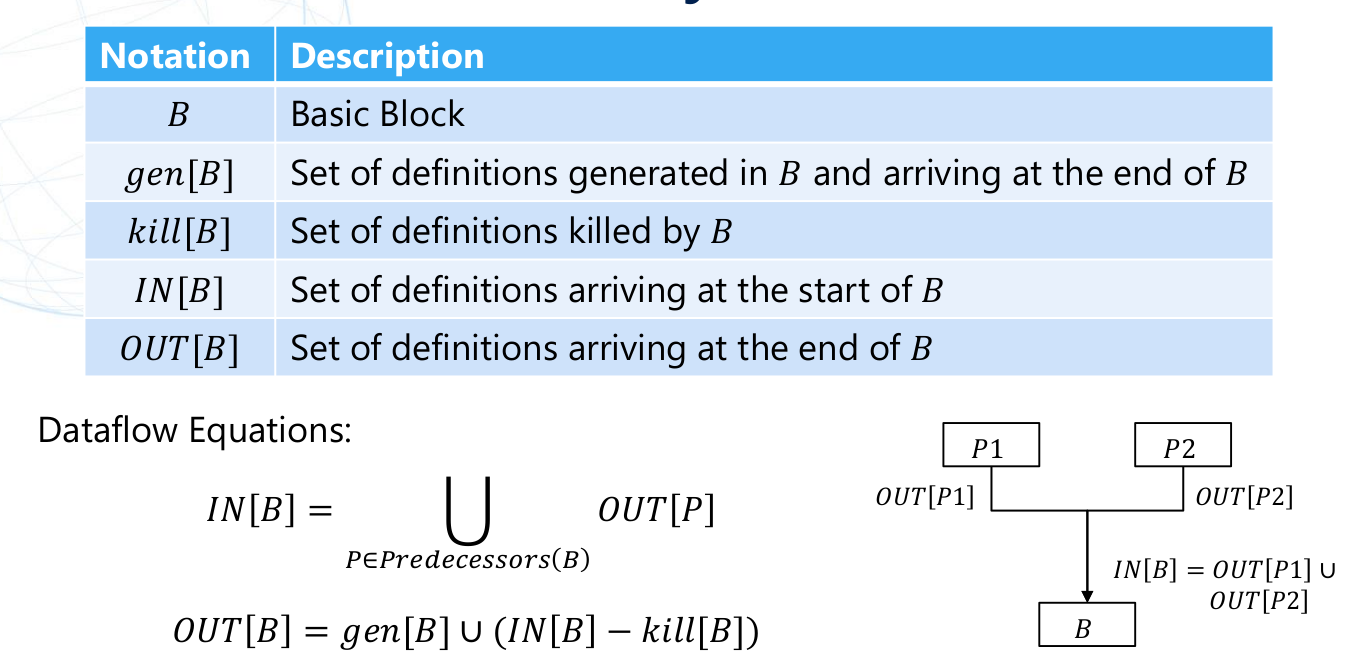

An overview of how Reachability Analysis work can be shown in the following picture from Yuma’s Course:

The theoritical model to apply Reachability Analysis is the following"

Liveless Analysis #

- Backward dataflow analysis

- Analyze whether the value x in the program point p may be used when following the edge starting from p in the flow graph with respect to x

- Application:

- Dead code elimination

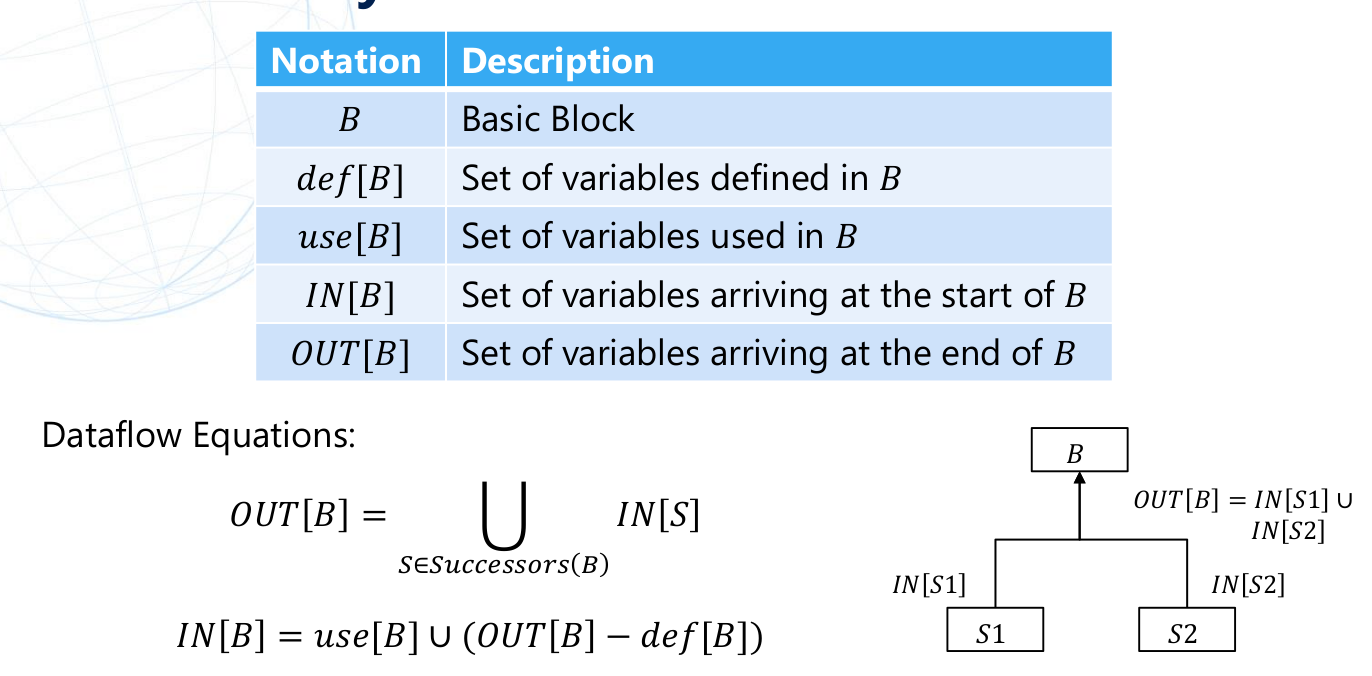

An overview of how Liveless Analysis work can be shown in the following picture from Yuma’s Course:

The theoritical model to apply Liveless Analysis is the following"

Both reachable definition analysis and liveness analysis are IR optimization techniques used by a compiler backend, and are also useful for binary analysis.

Practical Example. Deobfuscating OLLVM’s Instruction Substitution Pass #

For this example we will be using the given example compiled with o-llvm -sub flag to enable OLLVM’s Intruction Substitution Pass.

#include <stdio.h>

unsigned int target_function(int n) {

int a,b,c,r;

a = 12;

b = 56;

c = 127;

r = a + b + c + n;

return r;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int n = target_function(argc);

printf("n=%d\n", n);

return n;

}

Since we need a framework to lift the code to an IR to apply these types of optimization analyses, we can use MIASM’s Data Flow Analysis modules to deobfuscate transformations such as instruction substitution, dead/junk code or constant unfolding.

MIASM has a simple way of retrieving and lifting the subject function to MIASM IR:

# Opening Target File and Storing it in a 'Container' Object

cont = Container.from_stream(open(args.target, 'rb'))

# Instantiating disassembler

machine = Machine(args.architecture if args.architecture else cont.arch)

dis = machine.dis_engine(cont.bin_stream, loc_db=cont.loc_db)

# Disassembling and Extracting CFG

asmcfg = dis.dis_multiblock(int(args.addr, 0))

# Extracting IR archive and IRCFG

ir_arch = machine.ira(cont.loc_db)

ircfg = ir_arch.new_ircfg_from_asmcfg(asmcfg)

# Simplifying IR

deadrm = DeadRemoval(ir_arch)

entry_points = set([dis.loc_db.get_offset_location(args.addr)])

init_infos = ir_arch.arch.regs.regs_init

cst_propag_link = propagate_cst_expr(ir_arch, ircfg, args.addr, init_infos)

# deadrm(ircfg)

# remove_empty_assignblks(ircfg)

# This line simplifies the IR with the same features as above and more

ircfg.simplify(expr_simp_high_to_explicit)In order to do this we can do the following:

# Instantiate an LLVM context and Function to fill

context = LLVMContext_IRCompilation()

context.ir_arch = ir_arch

func = LLVMFunction_IRCompilation(context, name="test")

func.ret_type = llvm_ir.VoidType()

func.init_fc()

...

# IRCFG is imported, without the final "ret void"

func.from_ircfg(ircfg, append_ret=False)

# Finish the function

func.builder.ret_void()

# Parsing LLVM IR

M = llvm.parse_assembly(str(func))

M.verify()

# Initialising Native Exporter

llvm.initialize()

llvm.initialize_native_target()

llvm.initialize_native_asmprinter()

# Optimisation to clean value computation

pmb = llvm.create_pass_manager_builder()

pmb.opt_level = 2

pm = llvm.create_module_pass_manager()

pmb.populate(pm)

pm.run(M)

# Generate Binary output

target = llvm.Target.from_default_triple()

target = target.from_triple('i386-pc-linux-gnu')

target_machine = target.create_target_machine()

obj_bin = target_machine.emit_object(M)

obj = llvm.ObjectFileRef.from_data(obj_bin)

open("./%s-%s.o" % (args.target, hex(int(args.addr, 0))), "wb").write(obj_bin)After running the previous script, we will see it will generate an ET_REL type ELF file containing the native version of our deobfuscated function by optimization. The following is the result of this:

As we can see in the previous screenshot, there is some dead code resident in the optimized function. This dead code represents the local variables used in the obfuscated (and original) version of the function.

Data Flow Analysis and optimizations are restricted to memory writes along with other constraints such as variables involved in conditional jumps. Despite this, we can clearly see that Data Flow Analysis can be very effective for instruction subtitution deobfuscation giving us a simplified version of what the function may have looked like after and even before obfuscation.

As we mentioned there are some additional contraints while removing some of the dead code after simplification, such as memory writes or variables needed for conditional branches. In regards to conditional branches, in the next section we will cover the concept of opaque predicates and what we can do to indentify and mitigate them.

Opaque Predicates #

Opaque predicates in a nutshell is a commonly used technique in code obfuscation intended to add complexity to control flow usually implemented as conditional branches although these conditional branches have a deterministic control flow.

A simple example of what opaque predicates are can be shown in the following C code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main (int argc, char **argv) {

int a=3, b=4;

if(a == b) { // opaque predicate

puts("This is never going to execute");

return 1;

}

puts("predifined control flow");

return 0;

}This same concept can be extrapolated to more complex equalities/conditions usually appearing in high volume on a subject obfuscated application. Depending on the implementation sophistication of this technique, control flow clarity can be highly affected and therefore the interpretation and time of analysis of a subject application.

Circumvention #

One approach to identify opaque predicates is to use Symbolic Execution along with an SMT solver in order to check feasibility on conditional branches.

How it works:

- Execute a program sequentially while treating input values as symbols that represent all possible values.

- Add constraints on symbols.

- Path Constraint: Constraints to execute a path.

- Symbolic Store: Updated symbol information.

- When the target address of the conditional jump is reached, solve the constraints with a SMT solver and get a concrete input value.

- Need to convert IR to SMT solver-acceptable expressions.

Opaque predicates have a deterministic feasibility regardless of input values. Therefore, we can invoke a SMT solver at every conditional branch and verify whether there is an input value that evaluates the condition to a True or False result. If a subject conditional branch is not dependant on a input value the branch should be an opaque predicate. We can apply the technique discussed above and attempt to detect opaque predicates via Symbolic Execution + SMT solver.

Practical Example. Deobfuscating X-Tunnel Opaque Predicates #

The binary file we are going to use for this example is the following:

X-Tunnel: a979c5094f75548043a22b174aa10e1f2025371bd9e1249679f052b168e194b3def explore(ir, start_addr, start_symbols,

ircfg, cond_limit=30, uncond_limit=100,

lbl_stop=None, final_states=[]):

def codepath_walk(addr, symbols, conds, depth, final_states, path):

...

# Instantiate MIASM Symbolic Execution Engine

sb = SymbolicExecutionEngine(ir, symbols)

for _ in range(uncond_limit):

if isinstance(addr, ExprInt):

# recursion delimiter

if addr._get_int() == lbl_stop:

final_states.append(FinalState(True, sb, conds, path))

return

# Append all executed Paths

path.append(addr)

# Run Symbolic Engine at block

pc = sb.run_block_at(ircfg, addr)

# if IR expression is a condition

if isinstance(pc, ExprCond):

# Create conditions that satisfy true or false paths

cond_true = {pc.cond: ExprInt(1, 32)}

cond_false = {pc.cond: ExprInt(0, 32)}

# Compute the destination addr of the true or false paths

addr_true = expr_simp(

sb.eval_expr(pc.replace_expr(cond_true), {}))

addr_false = expr_simp(

sb.eval_expr(pc.replace_expr(cond_false), {}))

# Adding previous conditions of previous

# blocks in path to satisfy reachability of current block

conds_true = list(conds) + list(cond_true.items())

conds_false = list(conds) + list(cond_false.items())

# Check feasibility of True condition on conditional branch

if check_path_feasibility(conds_true):

# If True path is feasible, continue with Symbolic Execution

codepath_walk(

addr_true, sb.symbols.copy(),

conds_true, depth + 1, final_states, list(path))

else:

# If not, store the current block and stop recursion

final_states.append(FinalState(False, sb, conds_true, path))

if check_path_feasibility(conds_false):

# If False path is feasible, continue with Symbolic Execution

codepath_walk(

addr_false, sb.symbols.copy(),

conds_false, depth + 1, final_states, list(path))

else:

# If not, store the current block and stop recursion

final_states.append(FinalState(False, sb, conds_false, path))

return

else:

# If current IR expression is not a Condition,

# simplify block expresion

addr = expr_simp(sb.eval_expr(pc))

# Append Final state

final_states.append(FinalState(True, sb, conds, path))

return

# Start by walking function from its start address

return codepath_walk(start_addr, start_symbols, [], 0, final_states, [])- Symbolically Execute every block in current function until it finds a conditional IR expression (which would be the same as a conditional instruction in its native representation).

- Once this conditional expression is reached, we then evaluate both the branch destination address if the condition would be satisfied and if it wouldn’t accordingly.

- When we have identified the two different branch addresses, then we compute the feasibility of each subject branch (which includes all previous conditions to reach to the designated destination address) and if its feasible we continue symbolically executing the branch. If not we mark that current path as finished and we store it.

The feasibility of the branch condition can be done via MIASM’s z3 SMT Solver Translator:

def check_path_feasibility(conds):

solver = z3.Solver()

for lval, rval in conds:

z3_cond = Translator.to_language("z3").from_expr(lval)

solver.add(z3_cond == int(rval.arg))

rslt = solver.check()

if rslt == z3.sat:

return True

else:

return False...

# The IR nodes in final_states array are the path nodes that were executed.

# We collect the 'lock_key' or block labels of each of the nodes executed

for final_state in final_states:

if final_state.result:

for node in final_state.path_history:

if isinstance(node, int):

lbl = ircfg.get_loc_key(node)

elif isinstance(node, ExprInt):

lbl = ircfg.get_loc_key(node._get_int())

elif isinstance(node, LocKey):

lbl = node.loc_key

if lbl not in executed_lockey:

executed_lockey.append(lbl)

# We then collect the non-executed blocks by comparing the executed ones

# with the totality of the blocks in the IRCFG

for lbl, irblock in viewitems(ircfg.blocks):

if lbl not in executed_lockey:

unexecuted_lockey.append(lbl)

...def to_idc(lockeys, asmcfg):

header = '''

#include <idc.idc>

static main(){

'''

footer = '''

}

'''

body = ''

f = open('op-color.idc', 'w')

for lbl in lockeys:

asmblk = asmcfg.loc_key_to_block(lbl)

if asmblk:

for l in asmblk.lines:

print(hex(l.offset))

body += 'SetColor(0x%08x, CIC_ITEM, 0xc7c7ff);\n'%(l.offset)

f.write(header+body+footer)

f.close()

This can help us to figure out the logic of the implementation of the subject opaque predicates. Once this is clear, we can then write a solution to patch the binary to obtain a more clear view of the function’s control flow to apply further analysis to it such as optimizations or data flow analysis after opaque predicates are removed. I decided to write a solution to remove X-Tunnel’s opaque predicates by using radare2 via its r2pipe Python binding:

def remove_xtunnel_op(lockeys, asmcfg):

# Opening File in r2

r2 = r2pipe.open("./x-tunnel.bin", ["-w"])

# applying reference analysis

r2.cmd("aar")

# iterating for each block label

for lbl in lockeys:

# retrieving block from label

asmblk = asmcfg.loc_key_to_block(lbl)

if asmblk:

for l in asmblk.lines:

# seeking to address of instruction

r2.cmd("s %s" % hex(l.offset))

# checking if there is any xrefs to

# current instruction

xref = r2.cmdj("axtj")

if xref:

# retrieving the reference source address

xref_from = xref[0]['from']

# retrieving the opcode

opcode = xref[0]['opcode']

# seeking to reference source address

r2.cmd("s %s" % hex(xref_from))

# changing opcode for nop if its a je or a non

# conditional jump if its any other branch instruction

r2.cmd("wao %s" % ("nop" if 'je' in opcode else "nocj"))

# seek back to original block instrution

r2.cmd("s %s" % hex(l.offset))

# patching instruction with a nop

r2.cmd("wao nop")

# seeking to previous instruction

r2.cmd("so -1")

# retrieving its opcode

opcode = r2.cmdj("pdj 1")[0]['opcode']

# if its a jne, change it to its

# non-conditional form

if 'jne' in opcode:

r2.cmd("wao nocj")After applying this script we can obtain results as follows (function at 0x40A6A0):

This approach can work for deterministic opaque perdicates although it has the following limitations:

- Path exploration algorithm can be very slow.

- SMT solver may have difficulties to solve specific contraints such as cryptographic schemes or hashing algorithms.

- Possibility of Path Explosion if input-dependant loops or recursion are found among other techniques.

There are known attacks against Symbolic Execution Analysis:

- Input Dependant loops.

- Range Dividers.

Another approach to detect opaque predicates: Abstract Interpretation (TODO. Some nice reference by Rolf Rolles)

In the following section we will cover an approach to detect Range Dividers and how we can circumvent them.

Range Dividers #

Range dividers are branch conditions that can be inserted at an arbitrary position inside a basic block, such that they divide the input range into multiple sets.

A simple example to illustrate this technique can be shown below:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

unsigned char *str = argv[1];

unsigned int hash = 0;

for (int i = 0 ; i < strlen(str); str++ , i++) {

char chr = *str - 0x20;

switch (chr) {

case 1:

hash = (hash << 7) ^ chr;

break;

case 2:

hash = (hash * 128) ^ chr;

break;

case 3: // obfuscated version of case 1

break;

...

default: // obfuscated version of case 1

break;

}

}

...

}- Branch execution is dependant on an input value

- All predicate branches have the same semantic meaning

- Robust against Symbolic Execution/Abstract Interpretation

- Almost like a n-way Opaque Predicate

The effectiveness of a range divider predicate against symbolic execution depends on:

- Number of branches of the predicate

- The number of times the predicate is executed

Circumvention #

An approach to identify Range Dividers is by Semtantic Equivalence Checking. Semantic Equivalence is an apporach to identify if two given sets of instructions have the same behavior based on the following premise:

- Same Code: Syntactically Equivalent

- Same Behavior: Semantically Equivalent

How it works:

- Perform Symbolic Execution per basic block on a given function.

- Check for basic blocks semantic and syntactic equivalence within a given function.

- Can be also seen as Semantic basic block diffing

Practical Example. Deobfuscating Asprox Range Dividers #

The binary file we are going to use for this example is the following:

Asprox: c56792bea8ac5fbf893ae3df1be0c3c878a615db6b24fd5253e5cbbc2e3e1dd3 ...

# enumerate all blogs in target function

target_blocks = []

for cn, block in enumerate(asmcfg.blocks):

target_blocks.append(block)

results = {}

# iterate over all blocks to select src block

for src_blk in target_blocks:

# retrieve src block label from src block

src_ldl = src_blk._loc_key

# Skip a basic blocks containing only single instruction

if len(src_blk.lines) == 1 and src_blk.lines[0].dstflow():

continue

# iterate through all blocks again

# to select dst block

for dst_blk in target_blocks:

# retrieve dst block label from dst block

dst_ldl = dst_blk._loc_key

# Skip a basic block containing only single instruction

if len(dst_blk.lines) < == and dst_blk.lines[0].dstflow():

continue

# Skip if src and dst block are the same block

if src_ldl == dst_ldl:

continue

# Skip if src and dst blocks have already been matched

if (src_ldl, dst_ldl) in results.keys() or \

(dst_ldl, src_ldl) in results.keys():

continue

# Check for syntax equivalence

r_syntax = syntax_compare(src_blk, dst_blk)

if r_syntax:

# If the syntax of two blocks is same, then the semantics of them is also same.

r_semantic = True

else:

# Check for semantic equivalence

r_semantic = semantic_compare(src_blk, dst_blk, ir_arch0, ir_arch1, asmcfg)

# save results of syntax and semantic checks

results[(src_ldl, dst_ldl)] = [(r_syntax, r_semantic)]

...def syntax_compare(blk0, blk1):

# if blocks do not contain the same

# number of instructions return

if len(blk0.lines) != len(blk1.lines):

return False

# iterate through all instructions in blocks

for l0, l1 in zip(blk0.lines, blk1.lines):

# if intruction is a branch

if str(l0)[0] == 'J':

# retrieve instruction opcode

instr0 = str(l0).split(' ')[0]

instr1 = str(l1).split(' ')[0]

if instr0 != instr1:

return False

# any other instruction

else:

if str(l0) != str(l1):

return False

return Truedef semantic_compare(blk0, blk1, ir_arch0, ir_arch1, asmcfg, flag_cmp=False):

# create empty IR CFG for src block

src_ircfg = IRCFG(None, ir_arch0.loc_db)

try:

# add src block to empty IR CFG

ir_arch0.add_asmblock_to_ircfg(blk0, src_ircfg)

except NotImplementedError:

return False

# create empty IR CFG for dst block

dst_ircfg = IRCFG(None, ir_arch1.loc_db)

try:

# add dst block to empty IR CFG

ir_arch1.add_asmblock_to_ircfg(blk1, dst_ircfg)

except NotImplementedError:

return False

# Check if blocks were added to their IRCFG correctly

if len(src_ircfg.blocks) != len(dst_ircfg.blocks):

return False

for src_lbl, dst_lbl in zip(src_ircfg.blocks, dst_ircfg.blocks):

# retrieve both src and dst blocks from their labels

src_irb = src_ircfg.blocks.get(src_lbl, None)

dst_irb = dst_ircfg.blocks.get(dst_lbl, None)

# symbolically execute them to evaluate

# semantic equivalence

r = execute_symbolic_execution(

src_irb, dst_irb,

ir_arch0, ir_arch1,

src_ircfg, dst_ircfg,

flag_cmp)

if r is False:

return False

return True ...

# Initialize symbol context with register context

for i, r in enumerate(all_regs_ids):

src_symbols[r] = all_regs_ids_init[i]

dst_symbols[r] = all_regs_ids_init[i]

# Instantiate Symbolic Execution Engine for src block

src_sb = SymbolicExecutionEngine(ir_arch0, src_symbols)

# for each IR instruction in src block

for assignblk in src_irb:

skip_update = False

# retrieve IR expression and operand in block

for dst, src in viewitems(assignblk):

# If operand involves EIP or ret

if str(dst) in ['EIP', 'IRDst']:

# skip symbolic execution

skip_update = True

# otherwise symbolically execute IR expression

if not skip_update:

src_sb.eval_updt_assignblk(assignblk)

# Instantiate Symbolic Execution Engine for dest block

dst_sb = SymbolicExecutionEngine(ir_arch1, dst_symbols)

# retrieve IR expression and operand in block

for assignblk in dst_irb:

skip_update = False

# If operand involves EIP or ret

for dst, src in viewitems(assignblk):

if str(dst) in ['EIP', 'IRDst']:

# skip symbolic execution

skip_update = True

if not skip_update:

# otherwise symbolically execute IR expression

dst_sb.eval_updt_assignblk(assignblk)

# set stack top for each symbolic engine

src_sb.del_mem_above_stack(ir_arch0.sp)

dst_sb.del_mem_above_stack(ir_arch1.sp)

...When this is done then we can start checking for semantic equivalence by evaluating each of the symbol’s contraints of each symbolically executed block:

...

# Retrieve all memory accesses from src and dst symbolic engines

all_memory_ids = [k for k, v in dst_sb.symbols.memory()] + [k for k, v in src_sb.symbols.memory()]

# iterate through all register and memory symbols

# from both symbolic engines

for k in all_regs_ids + all_memory_ids:

# keep iterating if symbol is EIP

if str(k) == 'EIP':

continue

# keep iterating if symbol is eflags

if not flag_cmp and k in [zf, nf, pf, of, cf, af, df, tf]:

continue

# retrieve value of symbol from each symbolic engine

v0 = src_sb.symbols[k]

v1 = dst_sb.symbols[k]

# keep iterating if symbol value is the same

if v0 == v1:

continue

# instantiate z3 SAT solver

solver = z3.Solver()

try:

# translate src symbol constraints to z3 readable form

z3_r_cond = Translator.to_language('z3').from_expr(v0)

except NotImplementedError:

return False

try:

# translate dst symbol constraints to z3 readable form

z3_l_cond = Translator.to_language('z3').from_expr(v1)

except NotImplementedError:

return False

# add equality condition to solver

solver.add(z3.Not(z3_r_cond == z3_l_cond))

# if condition was unsatisfiable

r = solver.check()

if r == z3.unsat:

# IR expression were equivalent

# keep iterating

continue

......

# save results of syntax and semantic checks

results[(src_ldl, dst_ldl)] = [(r_syntax, r_semantic)]

......

# create graph

G = nx.Graph()

# add nodes

G.add_nodes_from(target_blocks)

# add edges based on syntax/semantic equivalence

for k, v in viewitems(results):

# if blocks have syntactic or semantic equivalence

if v[0][0] or v[0][1]:

# add edge on block labels

G.add_edge(k[0], k[1])

random_colors = gen_random_color()

body = ''

# Iterate through the blocks which are equivalent

for n, conn_nodes in enumerate(nx.connected_components(G)):

if len(conn_nodes) == 1:

continue

for node in conn_nodes: # node is asmblk

# set the same color for equivalent nodes

if isinstance(node, LocKey):

asmblk = asmcfg.loc_key_to_block(node)

if asmblk:

for l in asmblk.lines:

body += 'SetColor(0x%08x, CIC_ITEM, 0x%x);\n' % (l.offset, random_colors[n])

else:

for l in node.lines:

body += 'SetColor(0x%08x, CIC_ITEM, 0x%x);\n' % (l.offset, random_colors[n])

header = '''

#include <idc.idc>

static main()

{

'''

footer = '''

}

'''

f = open('eq-color.idc', 'w')

f.write(header + body + footer)

f.close()After applying the previous script to a given obfuscated function (0x10009B82) and slightly refine the results, we can obtain the following:

After this is trivial to remove the range divider predicates from the subject function. All we need is to identify the initial conditional branch that diverges into each individual predicate and apply the correspondent chnages to it appropietly. The following are the before and after effects:

In the particular case of Asprox I found that it wasn’t implementing a high number of Range Divider predicates, usually two. Therefore it was trivial to clean the code after identifying them. All needed to do was to either patch the intial conditional branch that diverges into each individual predicate so that it becomes unconditional or patch the conditional branch in a way so that it becomes NOPed. We can apply either of these approaches accordingly to chose the predicate that will drive the control flow and remove the remaining ones.

Is also important to emphasize that the Range Divider cleaning process may not be as trivial if higher numbers of predicates where encountered or if the structure of the predicates would make each predicate to overlap with one another. Also lets not forget that this approach is assuming that the correct comparison unit is a basic block, which is true for Asprox predicates but is not necessarily generic. For example Tigress obfuscator implements Range Divider predicates on a function granuality. Therefore, this approach wont work, but could be adapted to support Tigress predicates re-defining the granuality for comparison and equivalence computation.

To finish this section on a high note, we can see that by marking blocks from a given function based on syntax and semantic equivalence can help us to indentify this obfuscation technique.